They were communists, and they knew all about parties. Having just boisterously celebrated May Day months before, the Bolsheviks set about in the summer and autumn of 1918 to plan the commemorations marking one year of workers power in Russia. Anatoly Lunacharsky, at the time serving in Petrograd as that oblast’s Commissar of the Union of Communes, recommended the celebration be “split into three parts: struggle, victory, the intoxication of victory … Initially the mood culminates, then attains its high point, and ends in general gaiety.” All this, in hopes of “repeating the emotional experience of the October revolution.” Lunacharsky’s aspirations were at least partially realized, as photographs and grainy video footage of the festivities attest. On November 9, cities throughout Russia teemed with colorful exhibitions, marching bands, and theatrical dramatizations of the seizing of the Winter Palace. At the district level, the planned centerpiece of the celebration was a gala concert at the local workers councils, where proletarian choruses had been formed for the occasion. The events, as bourgeois historians have noted in cautionary tones, provided the Bolsheviks an important opportunity to propagandize to the general population about the meaning of October.[1]

At the same time the party was overseeing its parties, it was also engaged in a bloody war against Russian and Western imperialist counterrevolutionaries. War communism, with its meticulous rationing of food staples, was in place. And industrial output was already in steep decline, soon to bottom out at one fifth of its 1913 levels. Discipline was the order of the day, and all of the state’s and society’s resources were bent toward winning the war. Notably, then, the Bolsheviks did not deem frivolity and “gaiety” as wasteful excesses in a time of sacrifice. They deemed them part of the revolutionary process of enhancing socialist solidarity within the working class. To this end, the Bolsheviks even arranged for entertainers to perform before Red Army soldiers on the front lines. What the party understood was that politics involved more than paper resolutions, workplace strikes, or even armed combat. It was about living, breathing people and their connections with one another. A political program, in their vision, was a political glue that bound together revolutionaries as they collectively struggled for a socialist future. A revolutionary party sometimes had to rely on multiple types of parties – festivals as well as military reconnaissance parties. Solidarity, trust, and mutual respect were, and are, integral to revolutionary party building. But at the same time, as this post will demonstrate through a case study of an episode involving Socialist Action, these bonds can also discourage Marxists from taking a stand in opposition to unprincipled behavior by their comrades.

On Parties and Propaganda Groups

Today we stand far removed from the context the Bolsheviks faced in 1918. Yet the central issues they faced remain our challenges—namely, all the issues connected to the crisis-prone epoch of decline. If that historical crisis is, as Trotsky described, a crisis of revolutionary socialist leadership, then it is also necessarily one of how existing aspirationally revolutionary organizations (AROs) attempt to develop leadership. This process was referred to by Leon Trotsky as centering on “the subjective factor.” Revolutionary consciousness is not automatic, does not spontaneously flow from participating in the capitalist workforce or even progressive political struggles. Revolutionaries have to be won over explicitly by a compelling political case combining forthright verbal persuasion backed by the unfolding of concrete events. The central paradox for revolutionary socialists at present, then, is how to propagate revolutionary consciousness if there is no revolutionary or even prerevolutionary situation against which workers can test the revolutionary aspects of the Marxist program against other programs.

In non-revolutionary periods, the gulf between program and concrete reality is bridgeable only by the advanced layers of workers—the vanguard. And the duty of AROs at present is to find and win over those advanced workers. As a result of the nearly-century-long betrayals of Stalinism, coinciding with aggressive assaults by a decaying capitalist system, AROs are going to start as small propaganda groups and likely remain that way for some time. Only when a substantial portion of vanguard workers has been brought into an ARO will it become a vanguard party in the proper sense, capable in its existing form of leading the working-class struggle to overthrow capitalism.

Propaganda groups of the Leninist type are intense. They include small numbers of like-minded people, deeply committed to a radically different (and better) vision of society, who spend many hours per week collectively engaged in often unpopular, thankless, and exhausting political work. As such, they aren’t a book-of-the-month club, and they aren’t grandma’s weekly knitting circle. They require mutual respect, trust, and equal principled treatment. They therefore combine a prefigurative aspect (the political unity of the vanguard portending the socialist unity of humankind), with a decidedly instrumental/political-combat aspect that renders dubious any ARO’s pretensions to prefiguring life under socialism.[2]

The central task of the ARO is to carry out the paper program, and in a way that cultivates the kind of cultural and social atmosphere necessary for a revolutionary party—or even propaganda group—to function healthily. These twin features of an ARO are also its selling points: they provide supporters with an exhilarating channel for trying to change the world, at the same time that they provide the individual participant with a sense of identity and community, often through social functions not directly related to political work. When a person joins the party, they join it in both senses of the word.

But maintaining the right balance between the twin pillars is difficult, especially when the destruction of the Eastern Bloc and the self-aggrandizing opportunism of the remaining Stalinist states has soured all but the most visionary from so much as entertaining the possibility of a society beyond capitalism. A book-length compendium of obituaries could be written enumerating the countless examples of AROs who have canonized destructive gurus, rode their “struggle sessions” into political oblivion, or revised key elements of their formal program to maintain what resembles a frat party more than a revolutionary party. One chapter in the book would have to be reserved for a group descended from the formerly Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party (SWP), which turned away from a revolutionary orientation in the early 1960s and explicitly disavowed Trotskyism in the midst of a series of sweeping purges in the early 1980s. From the debris emerged a Sisyphean group determined to reestablish the same organizational and political dynamics that had precipitated their own bureaucratic expulsions from the SWP. That group is Socialist Action (SA).

What Is Socialist Action?

Socialist Action was constituted in 1983 by 39 individuals who had been expelled from the Socialist Workers Party over the prior two years. They retained their affiliation to the United Secretariat (USec), and sought to carry on the political traditions of the SWP from the 1960s and 1970s. They therefore continued to uphold Cuba as a non-bureaucratized workers state in which Castro was leading a healthy revolutionary wing against anti-revolutionary bureaucrats seeking to consolidate a hardened caste. Similarly, the group contends that black people, “Chicanos,” and Native Americans in the United States constitute “nationalities” (nations without their own states) whose struggles for self-determination should be supported. Both positions are politically linked, representing opportunist adaptations to the New Left currents of the 1960s[3] – adaptations that drew them away from Trotskyism and in the direction of the liquidationism that Jack Barnes advanced even further in the early 1980s.

Another component of this trend, which stemmed from the atrophied state of the revolutionary workers’ movement following the McCarthy era, was a tendency to form popular fronts. The most notorious example of this was the National Peace Action Coalition, a front group that became one of the largest anti-Vietnam-War organizations in the United States at the small price of abandoning working-class political independence. The same methodology continues in the present SA, most notably in the group’s work with the Workers World Party (WWP) inside the United National Antiwar Coalition (UNAC). As former member Andrew Pollack, who was a prolific contributor to SA’s publications, described in his resignation letter:

“It believes it has no duty, as one would in a traditional united front, to criticize in its own name members of that united front such as Workers’ World Party who have promoted the virtues of neocolonial dictators such as Qaddafi, Ahmedinejad, and most recently Assad, with whom WWP and friends had a most pleasant tea while his troops and allies were butchering Syrian revolutionaries.”

The political consequences of this thoroughly opportunist and popular-frontist approach to a supposed “united front” are evident in a particularly clear form in a speech SA leader Jeff Mackler delivered before a plenary session of UNAC last year. After noting that UNAC was united around the slogan of self-determination for semi-colonial nations, Mackler insisted that “that right to self-determination means that we support Syria’s right to invite other nations to defend it against imperialist attack. And that means we don’t put on UNAC’s banners ‘Russia Out Now!’ or ‘Hezbollah Out Now!’ or ‘Iran Out Now!’ They are all victims of imperialism.” In his attempt to “unite” in a front with the WWP, Mackler not only refrained from issuing criticisms of that group’s horrendous genuflections to brutal semi-colonial tryants (as one would also refrain from doing to court bourgeois support in a popular front), but he then articulated the liberal position that, because Assad has a legal right under international law to invite other governments’ militaries into Syria, revolutionary socialists categorically must not oppose Assad’s decisions on that matter – a backhanded form of political support. The implicit agreement not to raise political criticisms with front partners morphed, right before the eyes of those in attendance, into outright endorsement of the WWP’s liberal “anti-imperialist” line.

Despite claiming continuity with the finest traditions of the SWP under James P. Cannon, the group’s politics reveals what it has actually inherited: the worst opportunist and liquidationist impulses of the International Secretariat of Michel Pablo and Ernest Mandel. It is not coincidental that SWP reunited with Mandel’s rump “Fourth International” (forming USec) in 1963 precisely over their shared orientation toward the Cuban Revolution.[4]

Socialist Action’s Youth Work

In addition to raising illusions in the Castros’ supposedly revolutionary bona fides and entering unprincipled propaganda blocs sui generis, Socialist Action maintains political contact with a number of youth organizations across the country. Known as “Youth for Socialist Action” (YSA – also the acronym of the SWP’s youth organization in the 1960s and 1970s), these groups are located primarily on college campuses and are ostensibly modeled off the framework of the early SWP’s understanding of “party-youth” relations. According to that model, youth organizations are organizationally independent but politically subordinate to the parent organization. In practice, the model entails the youth running their own organization – admitting new members, electing their leadership, and engaging in the same organizational matters that the parent organization does – while maintaining close political consultation with the parent organization to coordinate joint work and to iron out whatever political differences might develop from time to time. As the YSA claimed on its now-deleted web page, “Youth for Socialist Action is an independent organization.” And membership required agreement with the YSA’s “manifesto,” presumably drawn up in close consultation with SA itself before being democratically adopted by the new organization.

But as a Marxist with any experience in revolutionary politics can attest, practice does not always live up to theory. And so it was, at least with one branch of YSA. Membership in YSA at Central Connecticut State University (CCSU) did not entail submitting any applications, agreeing with any manifesto, or anything more than the New-Left approach of just showing up repeatedly to meetings. In other words, there was no political subordination of the members of this branch. As one comrade who has been active in the organization for some time says:

“At the first YSA meeting I ever attended, I asked about the relationship between SA and YSA since I was not sympathetic with SA’s politics and was not interested in joining or promoting their organization. I was told by an SA member who sat in at YSA meetings that it was not a group for SA. There were no [campus or branch] documents establishing either fraternal or paternal/subordinate relations between YSA and SA. If we were one of their youth groups during the past year and a half, then no one in YSA was aware of this.”

This political distance between CCSU’s YSA and SA was the result of years of evolution from the time the CCSU branch was established in 2007. Another member recalls:

“YSA and SA initially had a fairly standard party-youth organization relationship, where the party informed the youth organization programmatically and politically, while the youth organization had relatively autonomous leadership. However, as years passed, fewer and fewer members of YSA went on to join SA, or even remain in comradely affiliation with them. However, the president of YSA usually remained a member or a comrade in the process of becoming a member of SA. Despite the leadership being informed by SA, YSA still continued on its path of distancing itself from SA, culminating in the election of a non-SA member as president in Fall 2016. From this point on, YSA and SA existed as almost entirely separate organizations, though SA still expected (and attempted at times to enforce) organizational subordination. This gap, brought on largely by a distinct lack of communication, training, and education between SA and YSA, did not come about by any one decision. Rather, it was the decisive lack of investment of time and revolutionary training that engendered this divide. The YSA did not advertise itself as a Trotskyist student organization, but merely one welcoming of any student opposed to capitalism, racism, misogyny etc. This platform, based on vague notions of ‘social justice’, set the path for the YSA to evolve (or degenerate, depending on one’s point of view) into a broad church organization.”

YSA’s lack of political subordination, its dwindling political support for SA, posed significant problems for the latter group. CCSU’s YSA branch had begun using campus space and funding to host an annual “The Solution is Socialism” conference in coordination with Connecticut’s SA branch. And the dwindling number of SA supporters meant that SA would no longer be able to use the conference to advance its political objectives without running roughshod over what was, in YSA’s own words, an independent organization. SA’s solution to this dilemma was clear by the time of the second annual conference in the fall of 2017. In tried and true Mandelian fashion, it opted not to compromise in close coordination with YSA. Instead, it decided to dominate the planning process, all while accepting $2,500 dollars in YSA funds and utilizing valuable campus space at a college where its supporters had zero presence.

A member of YSA at the time again elaborates:

“SA’s relationship with YSA became further fraught with conflict in the process leading up to the second Socialism is the Solution conference. As with the first such conference, SA took control of nearly all planning of the event, leaving little room for input or discussion of the event’s details (such as speakers, topics, etc.) with YSA. Granted, YSA did not assert itself nearly as much as it should have in this process, but conversely, SA did not make any attempt to encourage their involvement. The only major attempt by YSA to invite a speaker independent of SA’s program, a member of the IBT (International Bolshevik Tendency) was met with harsh critique by SA, which attempted to prevent the IBT member in question from presenting as a main speaker at the conference.”

This bureaucratic attitude by SA to YSA also manifested itself in a relatively minor but telling slight at the conference. When the IBT speaker arrived at the conference hall and attempted to use one of the many empty tables to display his organization’s literature, a member of SA (who had not been in YSA for years) told him that new rules prohibited it. As explained by a member of YSA who was at the conference for its duration, “So at our conference, SA violated elementary workers’ democratic norms and refused to acknowledge any wrongdoing to our speaker for months, though they recognized to a number of people privately that what they did was wrong.” Predictably, Left Voice – a Morenoite outfit that is in a similarly unprincipled propaganda bloc sui generis with SA – was permitted to use a table to sell literature despite not receiving any permission from YSA members. When a comrade who was watching the conference online and was notified of the incident brought this to the attention of a Socialist Action member at the conference (whom we’ll call Stan Oregano), he was eventually told by Stan that an apology would be issued to the IBT supporter. But such promises were too little, too late.

Party Patriotism

Responses to Socialist Action’s bureaucratic behaviors were months in the making, and when they fully crystallized, they touched off a cacophony of sneering, backbiting, and unprincipled accusations from those inside the group. The breaking point came when CCSU’s YSA branch, sensing that maintaining nominal ties to SA would likely reproduce such bureaucratic episodes, voted to rename itself the Marxist Student Union as an effort to capture the group’s actual multi-tendency nature. A representative of the formerly named YSA group attended a Socialist Action function a couple of weeks later to relay the news, and was met with accusations that the decision was “immature” and would make SA’s organizing at the University of Connecticut more difficult. SA members unsuccessfully tried to persuade — in the name of “democracy” — the SA member to violate the trust of her comrades (and democratic centralist norms) by revealing how people within YSA voted, probably in the hopes of to trying to split the group and maintain some presence to continue exploiting the campus’s resources. (It seems splits which benefit their organization are okay, whereas those that do not, aren’t.) Around the same time, months after the conference, the comrade who was told an apology would be issued to the IBT supporter was notified that no such apology was ever issued. When he heard this, he recontacted Stan over Facebook and asked whether there was a reason for the hold-up or if such an apology would ever be sent. Stan read the messages but then did not respond. After a couple of additional attempts at following up, the comrade was blocked on Facebook. In spite of previous statements Stan made in which he conceded that his group had violated democratic norms in relation to the IBT supporter, he now seemed interested only in reflecting the silence of his organization.

Baffled by being blocked for raising a relatively minor issue, the comrade then wrote a post in a Marxist Facebook discussion group in which Stan is an administrator. The post gave a run-down of the situation involving the bureaucratic behaviors of SA before and during the conference, but – out of courtesy to the parties involved – left out specific names of the people and organizations involved. Before long, a supporter of SA from another branch (whom we’ll call Duane Bossi), apparently aware of the actual situation being referred to, accused the person who posted the thread of being petty, politically cowardly, and having “weird ideas” about how revolutionary organizations are supposed to function. When an actual YSA member at CCSU intervened in the conversation, expressing agreement with the political thrust of the initial post, Duane told that YSA member that he was engaging in “personal gossip” and “griping.” When the comrade who wrote the initial post recommended to Duane that he should consider looking into the SWP’s early literature on party-youth relations, a supporter of Left Voice (whom we’ll call Elvira Lopez), jumped headlong into the discussion thread and fulminated that the post was apolitical and did not belong in the group. She also likely requested that the post be removed – which it was, by an admin who is not affiliated with SA (who, by chance, spoke the following day at a Socialist Action function).

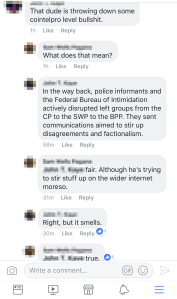

As this series of rather silly and surreal events was unfolding, something a bit more serious began to occur on the Facebook timeline of Stan Oregano. Thinking the comrade he had blocked would not able to gather what was happening on his timeline, Stan and a number of other SA supporters, apparently incensed about the post, began complaining there. Stan’s initial post opined, “Vaguebooking is the least Cannonist way to deal with a problem,” but was soon followed by a comment from an SA supporter (whom we’ll call Katie Johns) that stated, “That dude is throwing down some cointelpro level bullshit.” When Stan inquired what Katie meant, Katie replied, “In the way back, police informants and the Federal Bureau of Intimidation actively disrupted left groups from the CP to the SWP to the BPP. They sent communications aimed to stir up disagreements and factionalism.” Stan, now understanding what Katie meant, agreed: “Fair. Although he’s trying to stir stuff up on the wider internet moreso.” “Right, but it smells,” concurred Katie. (A CCSU YSA member attempted to intervene in the discussion in order to ask what Stan thought the right approach would be to addressing the apology issue, but was then promptly blocked also.)

The term for the dangerously unprincipled behavior in which Stan and Katie were engaging is “snitchjacketing,” and it is actually against the very rules of the Marxist Facebook group in which Stan is an administrator, for good reason. When the comrade who was being snitchjacketed discovered what was happening, he proceeded to message Katie Johns (a long-time SA member with whom he had had good and principled political discussions regarding Syria on prior occasions) in order to call out the poor behavior. Katie Johns’s initial response was to accuse the comrade of “trolling and trying to disrupt his organization” and “trying to undermine [Katie’s group’s] youth work.” The comrade replied by pointing out that it was far from trollish to highlight the undemocratic nature of strong-arming the planning of a conference hosted by an organizationally independent group, followed by unilaterally telling a speaker at the conference he could not display his political literature on an empty table without so much as the consent of the host organization. Katie Johns’s reply, which belongs in a museum exhibit as an example of self-serving opportunism was, “Isn’t that a bullshit argument? YSA and SA are linked. The YSA on that campus /organized/ the conference. You do realize that the way you get space on campus without paying through the nose is by having a campus group do it? Right? Insofar as the IBT goes. Yeah, they were initially told that they couldn’t table but I understand that was reversed.” The decision had not, in fact, been reversed – something Katie should have known as a speaker at that very conference.

The following day the IBT supporter finally received his written apology. That same day, the comrade who tried raising the issue in the Marxist discussion group realized that all the SA contacts he routinely connected with through Facebook had, most likely in a coordinated fashion, chosen to block him. Such actually petty reactions – “snitchjacketing,” name calling, attempts to manipulate comrades in a separate organization to violate democratic-centralist norms – were clear signs of a collective inability to respond to the actual political content of the organizational issues raised. Moreover, they were sectarian violations of principle in which behaviors that they would otherwise repudiate in other people or organizations were adopted shamelessly and used as a cudgel to advance the narrow interests of Socialist Action. For Stan and Duane and Katie, along with other SA supporters who had knowledge of the events and opted simply to block the comrade (whom we’ll call Fritz von Stevens and Darren P. Whitney), loyalty to the party was more important than loyalty to the democratic norms and standards of comradeliness upon which the working-class movement depends for its success. Such are the risks of being in a small and insular organization, at a time of low class consciousness, and finally feeling that you have arrived at the right party.

[1] The quotes and descriptions of the events surrounding the planning of the anniversary celebrations is drawn from Alexander Rabinowitch, The Bolsheviks in Power: The First Year of Soviet Rule in Petrograd (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 2008). In the first-anniversary issue, the lead story of Pravda, written and signed by Joseph Stalin, attested: “All the work and practical organization of the rising was carried out under the immediate leadership of Trotsky, the chairman of the Petrograd Soviet. We can state with all certainty that we owe the garrison’s prompt adherence to the Soviet cause and the skillful organizations of the work of the Party’s Revolutionary War Committee first and foremost to Comrade Trotsky.”

[2] As Trotsky indicated, “A revolutionary organization is not the prototype of the future state, but merely the instrument for its creation.” One reader of In Struggle’s previous blog post on how the democratic and centralist form of a revolutionary organization represented prefigurative principles (principles that would also govern international society under socialism) mistook that position for the far different claim that revolutionary organizations are, in the content of their activities, a window into the future or a “prototype” – as if socialist society would look like a small propaganda group or even a mass revolutionary party. On the contrary, as the contextual discussion of the above Trotsky quote makes clear, the principle of centralism (unity) cannot be fetishized or stripped from the concretes that define its political content. Revolutionary workers fight to unite the working class (centralize it around a socialist program), but sometimes against other forms of “centralism” (the example Trotsky gave is the centralized oppression of nationalities under the Tsar – all united in their subjection to Russian chauvinism), even if that struggle would, temporarily at least, result in greater political fragmentation along national divisions.

As with bourgeois democracy, these rather abstract prefigurative principles must always be subordinated to revolutionary class politics, which are always concrete. In Struggle stands behind the previous blog post’s argument that James P. Cannon had only a partial sense of democratic centralism, a sense of it as being little more than a temporary tool of struggle rather than a combination of principles that will also guide a future socialist society. Indeed, the paragraph from which the Trotsky quote is drawn implicitly takes the same position as In Struggle: unity (centralism and centrally authorized coordination at local levels)—a word which appears repeatedly in the chapter as a major theme—is what revolutionaries wish to achieve, but not just any kind of unity. Centralism will not suddenly become undesirable in an international system of administration. Quite the opposite will be the case, as it will be all the more essential.

[3] It must be remembered that in the late 1960s, the explicitly black-nationalist Black Panther Party was widely considered by young activists to be at the vanguard of an imminent revolution in the United States. The SWP also dipped its toe in the gay liberation movement, initiating a probe into the Gay Activists Alliance in 1971. For more on the formative role the Cuban Revolution played in the development of the New Left, particularly Students for a Democratic Society, see Richard E. Welch, Response to Revolution: The United States and the Cuban Revolution, 1959-1961 (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1985).

[4] It was this turn in 1963 that led to the bureaucratic expulsion of SWP members who opposed the Pabloist line on Cuba. Some of the expelled members later went on to form the Spartacist League, which, along with groups that split from it, maintains to this day the correct line on Cuba as a deformed workers state.

Actually the SWP didn’t use the term “nation” to describe Chicanos or Blacks. The Party made a distinction between a “nation” and an “oppressed nationality”. Also…why do you put ironic quotes around Chicanos?

LikeLike

Hi, David. Thanks for the response. I placed quotes around “Chicanos” to make clear that that was not my chosen terminology — it’s quite antiquated, and I think most today would use the term Latinx. As for the oppressed nation/nationality distinction, is this a distinction with programmatic implications? Does it have a history in Marxist political traditions?

LikeLike

I have changed the wording to be clear about the terminology, David. Thanks again.

LikeLike

In 2006 the Spartacist League gave critical support to Jeff Mackler, SA’s candidate for U.S. Senate in California. Read all about it: http://www.icl-fi.org/english/wv/876/votemackler.html

LikeLike